Pete Clarkson has a love-hate relationship with the plastic he turns into art.

As an artist, his sculptures made with ocean debris from the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve have earned him national acclaim, and permanent exhibitions in major institutions.

As a conservationist and park warden, he is dismayed at the toxic effects of ocean debris on nature.

Clarkson began making sculptures after his “dream job” as a national park warden brought him and his family to the West Coast of Vancouver Island more than 20 years ago, to work at the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve near Tofino. (He retired in 2020 and now works with the Coastal Restoration Society.)

Most of his colleagues had creative outlets such as music or carving, and he decided he needed an outlet, too. “I tried painting, photography, and carving. Nothing really worked,” he told West Coast Now.

What did fire Clarkson’s passion was pollution – specifically, plastic debris in the ocean. The junk that washed ashore in the park’s remote areas stayed there. “The Broken Group of Islands – wow! – it was a like a little mini-land fill,” he recalled.

Clarkson tried, but failed, to interest others in a clean-up. “That was depressing,” he recalled.

“But then I started looking at plastic objects, the way they were worn and weathered, and thinking about their back story. Every object had some human connection that really got me jazzed.”

He hauled some junk home and fashioned a “folk art” sculpture as a going-away present for some colleagues.

“They just loved it,” he recalled – and his art career was born.

He kept harvesting debris, and by 2005 he had enough sculptures to host his own art show in Tofino: “I friggin sold so much stuff, and the feedback was phenomenal. I was hooked.”

Clarkson expanded his art, eventually creating a workshop on his family’s property – but always as a sideline to his jobs.

“I don’t enjoy marketing,” he explains.

As it turned out, Clarkson didn’t have to market his work – the market came to him.

After his original show, word about his sculptures got around. The 2011 Japanese tsunami had made ocean debris pollution a hot topic worldwide, and soon major institutions commissioned his work. One giant Clarkson piece now hangs in the water gallery of the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa.

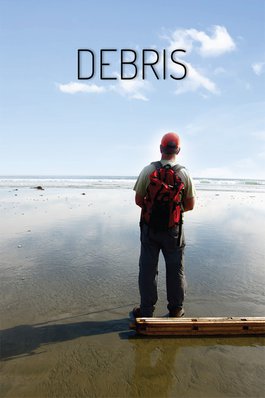

A National Film Board documentary about him, “Debris,” is free to stream. He has had several exhibits at the Vancouver Aquarium and on display in public venues in Ucluelet and Tofino.

Clarkson’s latest piece, “Classic Plastic,” was a collaboration with Tofino fabric artist Kim Leckey. The sculpture, made on a Tofino sidewalk, includes 565 discarded water bottles and caps wrapped in a discarded tarp shaped to resemble a waterfall.

Clarkson is the first to admit his art is difficult to define, but said his process of rearranging and looking at objects until an idea for a sculpture comes to mind, “elevates it from folk art to more fine art, I guess.”

“It’s been called environmental art, beach art, found-object sculpture and recycled art,” he notes on his website. “On one level it wounds me that the world is so overcome by debris, and yet I am often inspired by its sublime beauty, and the reminder it carries that we are all connected.”