New scientific research in the Great Bear Rainforest shows that wildflowers growing near dead salmon on B.C.’s spawning streams are more lush–with bigger blossoms or leaves–than plants that don’t benefit from fish carcasses.

It backs up earlier studies that suggest returning salmon deliver essential nutrients to B.C. forests. Unfortunately, the opposite is true: sharp declines in salmon populations also threaten species inland.

“This study affirms what Haíɫzaqv, other coastal First Nations people, and local gardeners have known for generations: salmon make excellent fertilizer,” quipped lead researcher Allison Dennert.

“Understanding the interconnection between ecosystems is incredibly important to our knowledge of how to protect them,” Dennert, a Ph.D. candidate at Simon Fraser University and Salmon Ecologist for the Raincoast Conservation Foundation, said in a university statement.

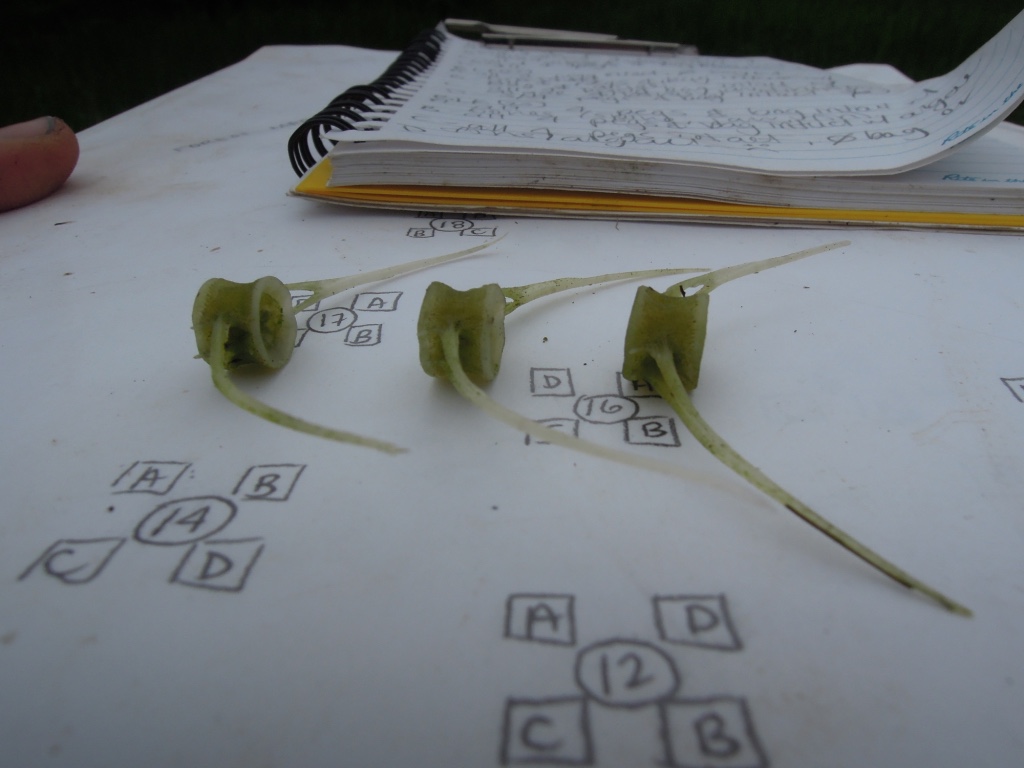

For three years, scientists left spring salmon carcasses near a remote river in Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) territory on B.C.’s Central Coast, then measured the effect on silverweed, yarrow, Douglas’ aster, and common red paintbrush.

“Some species of wildflower grew larger leaves where a salmon carcass was deposited, and in some years, some species grew larger flowers or produced more seeds,” said Dennert, who worked with SFU biology professors Elizabeth Elle and John Reynolds.

“Plants are the foundation of the ecosystem that we know and love in B.C.,” Dennert told West Coast Now in an interview. “They need nutrients deposited by salmon, and all of the rest of the birds, bears, and other animals rely on this ecosystem.”

The finding, published in a peer-reviewed science journal Royal Society Open Science, builds on previous research that showed a nitrogen isotope in some B.C. plants and animals came from salmon returning from the sea to spawn inland.

But these relationships are under threat, Dennert noted. Other recent research by SFU alumnus Will Atlas shows that “chum salmon abundance in the team’s study region declined almost 50 per cent within the last 15 years, and over 70 per cent within the last 50 years.”

Dennert said knowing the ocean and land systems are interconnected should change how governments manage ecosystems.

She said the study furthers the idea that “ecosystems don’t exist in isolation, and that what happens in one can influence the other.”