B.C.’s halibut fishers are sharpening their hooks and tuning up their boat engines for a 2023 season that could land the equivalent of a pound of fish for every British Columbian.

This year’s five million pound quota is down slightly from last year. But it still translates into $45 million worth of wild halibut harvested from North Coast waters and shipped worldwide. The season opens coastwide on March 10.

“We’re all wondering about the price,” Chris Sporer, executive manager of the Pacific Halibut Management Association, told West Coast Now, “but last year we heard of fishermen getting $9 to $9.50 a pound, sometimes more.”

“Halibut has become a fishery that’s a real backbone for the smaller vessel fleet, and a lot of people really depend on it.”

Chris Sporer

B.C.’s halibut stocks are in good shape after more than a century of commercial harvesting, thanks in part to careful management by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the International Pacific Halibut Commission (IPHC), a joint U.S.-Canada institution created by treaty in 1923.

Despite worrisome declines in some Alaskan waters, the IPHC says halibut stocks “are not considered overfished.”

That’s a big contrast from B.C.’s beleaguered salmon stocks and good news for the 600 to 700 fishers working the B.C. halibut grounds. Nearly 100 percent of their catch is landed at Port Hardy, Prince Rupert and Port Edward, where it is carefully counted before moving on for processing.

Image Source: Wild Pacific Halibut

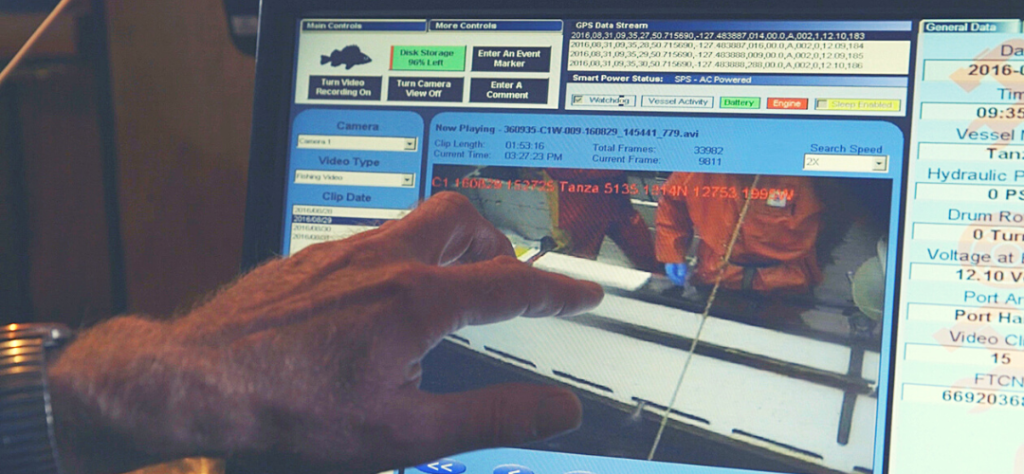

That dockside check is on top of “100 percent at sea” monitoring that sees each fish photographed as it comes on board by both wide angle and close-up cameras and registered on GPS. Electronic logs are sampled by fisheries officers and checked against written logs for accuracy. If there’s a discrepancy, a costly full audit may ensue.

Image Source: Wild Pacific Halibut

It all adds up to a fishery with a solid future that is producing annual returns for quota owners of 5.45 percent, according to a recent DFO analysis. Anyone hoping to buy halibut quota should be ready to offer $90 to $100 a pound.

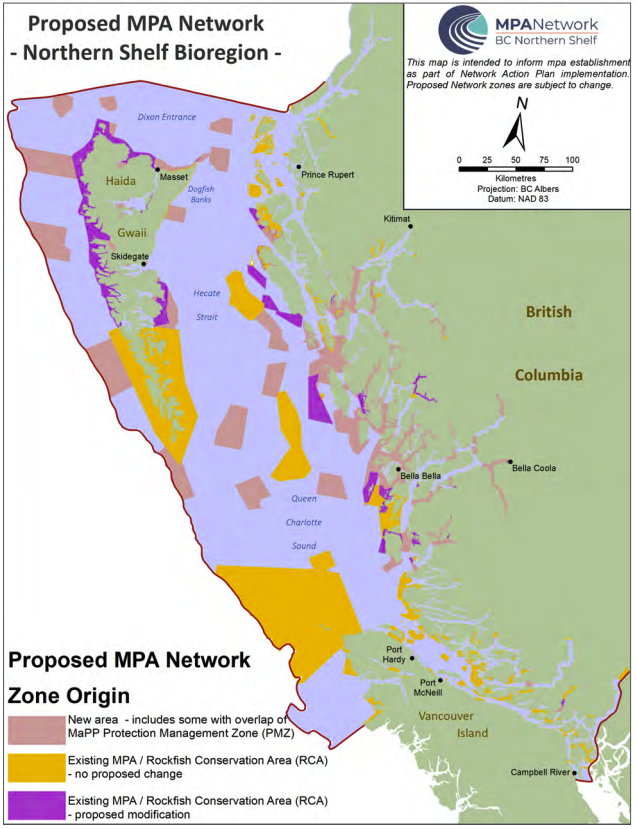

More than 90 percent of the commercial halibut catch comes from a vast expanse of coastal waters between Vancouver Island and Alaska known as the Northern Shelf Bioregion or Great Bear Sea, where Canada has endorsed a plan to create a network of marine protected areas.

Sporer and other fishermen have questions about how that network will operate.

“Halibut has become a fishery that’s a real backbone for the smaller vessel fleet,” Sporer says, “and a lot of people really depend on it. They’ve announced a network action plan and the different zones, but not the activities that will be permitted or not permitted in these zones.”

That uncertainty is a concern for the halibut fleet because closures in those zones “could have a big impact not just on the fishery but on the infrastructure” of small businesses it supports.

“Once you lose the critical infrastructure, you won’t get it back,” Sporer says.

But halibut harvesters are hopeful a consensus can be found to protect B.C.’s most prosperous small-boat fishery as marine protected areas expand, Sporer says. It happened in Haida Gwaii when waters around Gwaii Haanas won increased protection.

“It must be done in a way that takes the advice of Indigenous and non-Indigenous fish harvesters to meet those protection objectives and minimize impact on commercial fisheries,” he says.

As a former deckhand I fished the derby days and when the quota came in we deckhands did not get anything. I went back to university for over 7 years and took a Masters in Marine Ecology by working all the way through in fish plants on board boats — dogfish, ling cod, whatever — and then worked for First Nations and Tribes (on a Green Card). Eventually had a career of some 30 years but it still rankles that now there are programs to re-train oil workers and so on when fishermen like me never got a hand up at all.