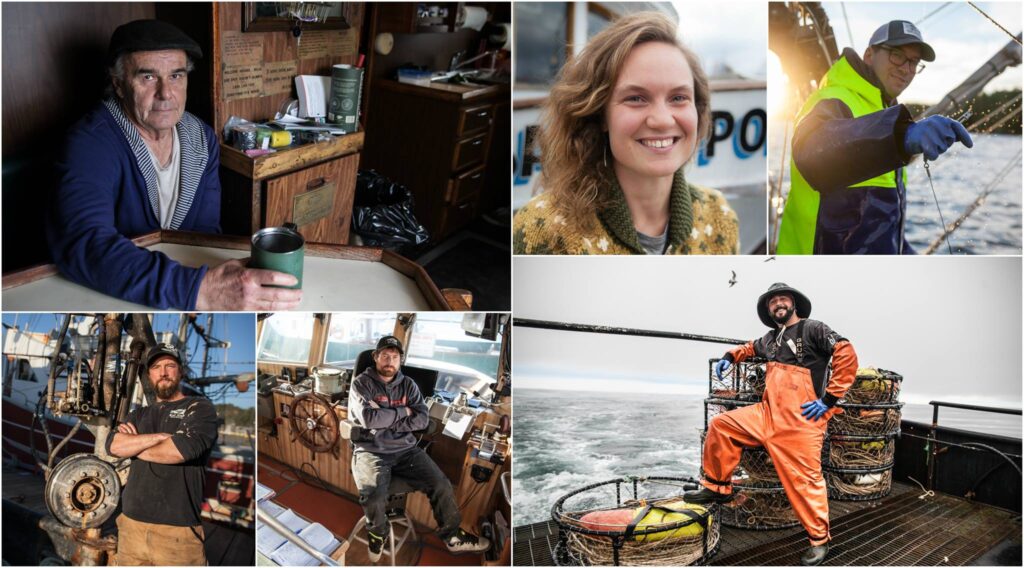

If you’ve ever wondered how, where, and when that Dungeness crab on your plate was caught, Prince Rupert crab fisher Chelsey Ellis can probably tell you its exact journey.

“Crab stocks are in good shape. With more than 220 vessels and 850 crew members, crab harvesters delivered $150 million in landings in 2021.”

Chelsey Ellis

But when it comes to charting the future of B.C.’s commercial fisheries, she says, “we’re on a knife edge.”

The basics seem sound. Crab stocks are in good shape. With more than 220 vessels and 850 crew members, crab harvesters delivered $150 million in landings in 2021, most of it for export.

Photo Credit: Chelsey Ellis Photography.

The problems are elsewhere, a combination of challenges that seem “like a perfect storm.”

The loss of critical infrastructure, like shipyards and marine hardware stores, combined with new government policies, adds to the uncertainty.

With the 2022 season drawing to a close, crab harvesters have seen total landings remain stable, but “the price was half what it was the year before,” Ellis says. “That’s hard to reconcile.”

The daughter of a Prince Edward Island potato farmer and lobster fisher, she has experienced commercial fishing on both coasts and at every step of the supply chain. Her remarkable career began a decade ago with an innovative project on “seafood traceability” of lobsters for the Vancouver-based organization Ecotrust Canada.

That work showed how tracking lobster from the ocean to the dinner table added value for harvesters and coastal communities by highlighting the industry’s commitment to conservation and quality. Harvesters can see how to maximize price, and consumers can be sure their food was sustainably harvested.

An invitation to apply those lessons to B.C.’s fisheries brought her to the West Coast, where she worked as a biologist, fisheries liaison, and deckhand, then went on to a leadership role in fisheries.

Along the way, she learned what it takes to work the deck of a crab boat aboard the Sea Harvest, a Prince Rupert vessel captained by third-generation fisherman Paul Edwards.

Now the mother of a two-year-old with another child on the way, Ellis manages her own photography business and acts as marketing coordinator for the B.C. Crab Fishermen’s Association.

She’s also executive director of the Area A Crab Association, which makes her the voice of 36 crab licence holders operating in the waters of Hecate Strait. They land about half of the total provincial crab catch.

Conservation is top of mind for crab harvesters. The Area A fleet, a leader in at-sea monitoring for at least 20 years, has installed sophisticated cameras to monitor and ensure regulations are followed in the fishery. They were the first fleet in North America to use this advanced camera technology

The association funds a softshell survey program and partners with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans to determine exactly when crabs begin moulting or renewing their shells. Once the shells begin to soften, fishing will stop until the major moult is over.

The MPA initiative “must be done through meaningful stakeholder engagement, proper community engagement, and with a rigorous socio-economic analysis.”

Chelsey Ellis

The Area A fleet alone supports more than 200 jobs at sea and many onshore, Ellis says, especially in Prince Rupert, “the Dungeness Crab Capital of Canada.” But she says critical infrastructure the fishery needs to survive is fading away.

Skippers are finding it harder and harder to recruit qualified deckhands. And the closure of key marine shipyards is forcing larger vessels like Sea Harvest to travel all the way to Vancouver to find a facility equipped to lift their boat from the water for maintenance. All this raises costs and eats into revenues for harvesters.

The recent announcement of a federally-backed network of marine protected areas in North Coast waters is another source of uncertainty. Her members support the conservation principles underlying marine protected areas, but harvesters say they have yet to feel properly engaged in the current process and have many unanswered questions.

The MPA initiative “must be done through meaningful stakeholder engagement, proper community engagement, and with a rigorous socio-economic analysis,” says Ellis. “We have to avoid huge unnecessary losses to fishing families, their communities and our coastal infrastructure.

“The government needs to be diligent and mindful to work with people who will be affected.”

The easiest way to do that? Listen to the expert knowledge of crabbers who spend all day on the water.