Radha Agarwal, Local Journalism Initiative

Students entering Grades 11 and 12 at Prince Rupert’s Charles Hay Secondary School in September will once again be able to take specialized science courses geared toward careers in the fishing industry.

The school, in collaboration with local stakeholders like Ecotrust Canada, Archipelago, Aero Trading and the North Coast Ecology Centre, is offering a specialized marine science program for a fourth year.

“The course focuses on the biological, the ecological, and the behavioural roles of local marine species. And the course builds upon skills relevant to marine science careers, environmental stewardship, ocean systems monitoring, and outdoor recreation,” said Vania Ling, course instructor at Charles Hay.

“Developing and teaching this course for the past three years has shown me that place-based learning integrating local ecosystems and indigenous knowledge offers numerous benefits. It enhances relevance and engagement by connecting students directly with their environment, fosters community connections and cultural appreciation, and promotes holistic and personalized learning.”

Vania Ling

They have been taking students for hands-on, place-based learning through field trips at fish processing plants and animal dissections. Students have monitored Halibut, Rockfish, and Geoduck.

They have been taught traditional ways of processing and cooking seafood. Charles Hay Secondary School is also currently building a smokehouse.

Indigenous Education Knowledge Keepers have shared their experience with food harvesting of locally found oolichan, herring eggs, and salmon.

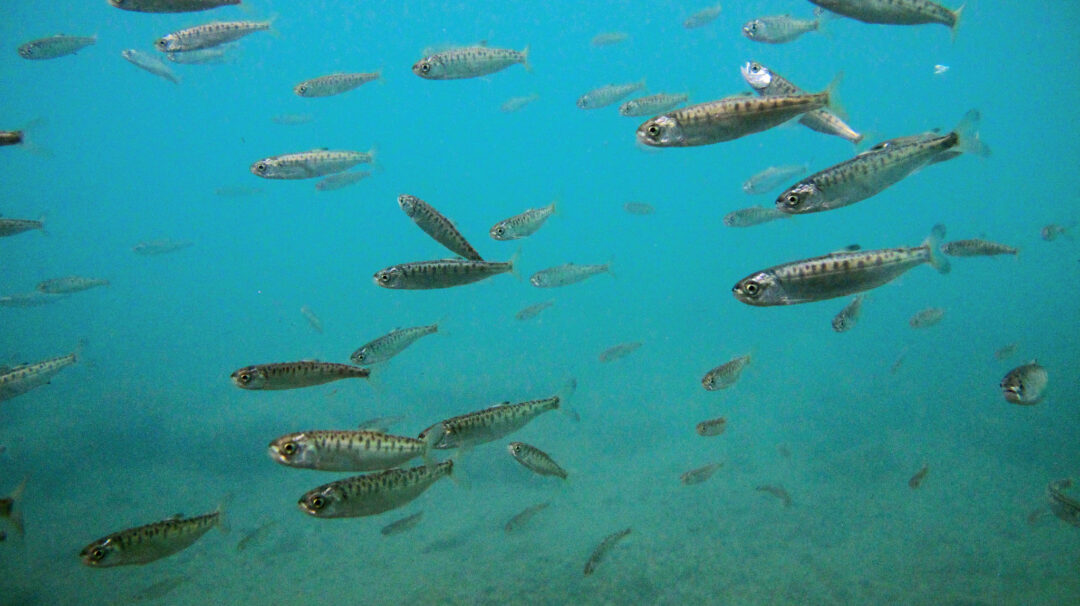

“Every year, we have a tank of salmon eggs and release the fry,” said Ling. The eggs are courtesy of the local Oldfield Creek Hatchery.

Ling said students are engaged in some independently created TikToks, which showcase their motivation and enthusiasm. They are learning the local Sm’algyax language and discussing traditional knowledge.

Ecotrust is a charity working toward nature-based solutions for industry and has sent visiting educators to the school since 2021.

They teach students about Dungeness crab bio-sampling, their fisheries monitoring program, and how fisheries industry jobs work in Prince Rupert.

Through their work with fish harvesters up and down the west coast of Canada, Ecotrust realized that developing locally-based fisheries monitoring programs is a prime opportunity to improve economic sustainability and achieve environmental sustainability in the commercial fishing industry.

They said the fishing industry is an integral part of a coastal community like Prince Rupert.

“We hope to see them in the fishing industry in the future years.”

Kathryn Bond, North Coast Fisheries project manager at Ecotrust.

“During our graduation ceremony, students mentioned in their vignettes that their most memorable moments of high school were place-based, and many especially loved fishing for oolichan. The students mentioned planning to continue to learn and preserve the Sm’algyax language as well as pursue careers in Marine Science,” said Ling.

She has already noticed that some students are entering the fishing industry by joining roles with stakeholders they met through this course. The school is continuing their endeavour to give students the opportunity to learn from the land.